This post was originally published on cloudlad.io

The most frequently used Terraform commands, plan, apply, and destroy, are the first things I learned when I started using Terraform. Primarily because those commands are a crucial part of Terraform’s cycle. Over time, as Terraform and its community grew, the features of Terraform grew in parallel. Now there are a lot more commands, options, arguments, and functions. Some are not used as often, and some do not even show when invoking the help menu.

In this blog post, I want to talk about the not-so-very common commands, arguments, and use cases.

Terraform Console

This command is my current personal fav, the console command. As per documentation it is most commonly used for experimenting with expressions and functions. As an added extra, if the command is invoked in a folder with an active Terraform state, it will read it from the configured backend. Inspecting and experimenting with the state with Terraform’s console can be fun!

Getting to it is as simple as typing in the command line:

$ terraform console

Now we can start “playing” with our state, provided there is something in it that we can fiddle with.

For the sake of this blog post let’s create a main.tf file with the following contents. The file is also available in my examples repo.

locals {

map = {

a = 1

b = 2

c = 3

}

}

resource "local_file" "private_key" {

content = jsonencode(local.map)

filename = "./map.json"

}

Needless to say, executing terraform init is necessary to pull the plugins and initialize the configured backend if there is any.

After, running terraform apply against this template, a JSON encoded file with the content of the local variable map will be created in the same folder. That is easy enough.

But what if I needed a YAML encoded file? I am also not sure how it will look. I prefer JSON, but I also like to have some comments.

I can check it on the fly by firing up Terraform console in the same folder and just YAML encoding the local map variable:

$ terraform console

> yamlencode(local.map)

<<EOT

"a": 1

"b": 2

"c": 3

EOT

Voila! We see how our file will look like if we’ve used the yamlencode function.

Why stop there, maybe I just need the value of the b key?

> yamlencode(local.map.b)

<<EOT

2

...

EOT

Swapping the keys and the values is also something that I might want?

> yamlencode({for k,v in local.map : v => k })

<<EOT

"1": "a"

"2": "b"

"3": "c"

EOT

Or just “trying” out the try function to see how it works exactly.

> try(yamlencode(local.map.d), 4)

4

Case in point. The flexibility that the terraform console provides when testing, troubleshooting, or simply playing around is immense.

Shell Autocomplete

This is one of the commands that do not appear when I invoke Terraform via the CLI. Having worked with Terraform for quite a while myself, I stumbled upon this command fairly recently. It lets you use shell tab-completion. As of writing this blog post, it works with bash or zsh shells only.

Running this will enable autocomplete for Terraform CLI. Re-reading the shell configuration or re-reloading a shell will activate it.

$ terraform -install-autocomplete

Lock Timeout

This is another very useful option, especially when running in an automated environment, such as a CI system. Imagine the scenario: we start two or more plans or apply jobs at a similar time. Naturally, Terraform will fail if it cannot get a lock for the state. With the option -lock-timeout instead of immediately failing, Terraform will retry getting the state lock for the duration specified in seconds. If Terraform cannot acquire a lock after the timeout has passed, it will fail with an error.

$ terraform apply/plan -lock-timeout=180s

Manual State Manipulation

Usually, I edit the state via Terraform CLI. Sometimes, though, I need to manually edit it. I do it via a pull, edit, and push cycle. These commands will work regardless of the type of backend configured. The most important things to remember when manually editing a state are:

- Validate the JSON before pushing.

- Increment the

serialkey by one.

“Pull-Edit-Push”

The following command will pull and write the current active state to the terraform_state.json file.

$ terraform state pull > terraform_state.json

Which has the following contents.

{

"version": 4,

"terraform_version": "1.0.4",

"serial": 1,

"lineage": "b538a863-c14e-c216-9309-e5e35f91468c",

"outputs": {},

"resources": [

{

"mode": "managed",

"type": "local_file",

"name": "private_key",

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"]",

"instances": [

{

"schema_version": 0,

"attributes": {

"content": "{\"a\":1,\"b\":2,\"c\":3}",

"content_base64": null,

"directory_permission": "0777",

"file_permission": "0777",

"filename": "./map.json",

"id": "e7ec4a8f2309bdd4c4c57cb2adfb79c91a293597",

"sensitive_content": null,

"source": null

},

"sensitive_attributes": [],

"private": "bnVsbA=="

}

]

}

]

}

I will remove the last element in the content parameter, and now the local state file looks like this:

{

"version": 4,

"terraform_version": "1.0.4",

"serial": 2,

"lineage": "b538a863-c14e-c216-9309-e5e35f91468c",

"outputs": {},

"resources": [

{

"mode": "managed",

"type": "local_file",

"name": "private_key",

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"]",

"instances": [

{

"schema_version": 0,

"attributes": {

"content": "{\"a\":1,\"b\":2}",

"content_base64": null,

"directory_permission": "0777",

"file_permission": "0777",

"filename": "./map.json",

"id": "e7ec4a8f2309bdd4c4c57cb2adfb79c91a293597",

"sensitive_content": null,

"source": null

},

"sensitive_attributes": [],

"private": "bnVsbA=="

}

]

}

]

}

After saving the file, “Pushing” the state back to its configured backend is as easy as:

$ terraform state push ./terraform_state.json

The “push” will fail if there’s something wrong with the state file. Otherwise, it shouldn’t provide any output.

Further verifying that the state edit is successful can be done by running either terraform plan or terraform apply.

The changes that Terraform will report attest to the successful manual state edit.

$ terraform apply

local_file.private_key: Refreshing state... [id=e7ec4a8f2309bdd4c4c57cb2adfb79c91a293597]

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

-/+ destroy and then create replacement

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# local_file.private_key must be replaced

-/+ resource "local_file" "private_key" {

~ content = jsonencode(

~ {

+ c = 3

# (2 unchanged elements hidden)

} # forces replacement

)

~ id = "e7ec4a8f2309bdd4c4c57cb2adfb79c91a293597" -> (known after apply)

# (3 unchanged attributes hidden)

}

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 1 to destroy.

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value: yes

local_file.private_key: Destroying... [id=e7ec4a8f2309bdd4c4c57cb2adfb79c91a293597]

local_file.private_key: Destruction complete after 0s

local_file.private_key: Creating...

local_file.private_key: Creation complete after 0s [id=e7ec4a8f2309bdd4c4c57cb2adfb79c91a293597]

Apply complete! Resources: 1 added, 0 changed, 1 destroyed.

As expected, Terraform reverts back to the state as instructed by the configuration in the main.tf. template.

JSON Instead Of HCL

The use case for this capability is quite interesting. I can programmatically generate Terraform templates using the JSON syntax. The only requirement is for the filename to have the extension tf.json. Otherwise, Terraform will not pick the configuration up.

I can convert the example above to JSON like so:

{

"locals": {

"map": {

"a": 1,

"b": 2,

"c": 3

}

},

"resource": {

"local_file": {

"private_key": {

"content": "jsonencode(local.map)",

"filename": "./map.json"

}

}

}

}

I would reckon it’s unusual to generate a JSON encoded file using the JSON syntax.

It is a very appealing feature I imagine is being actively used out there.

Terraform Graph

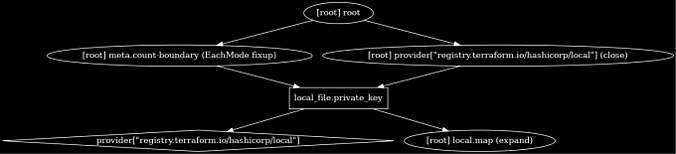

Not the most widely used Terraform command, but most definitely uncommon. It generates a DOT (graph description language) file that I can use to render an image in a well-known format, such as PNG. Running this command in the example state yields a chart description configuration.

$ terraform graph

digraph {

compound = "true"

newrank = "true"

subgraph "root" {

"[root] local_file.private_key (expand)" [label = "local_file.private_key", shape = "box"]

"[root] provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"]" [label = "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"]", shape = "diamond"]

"[root] local_file.private_key (expand)" -> "[root] local.map (expand)"

"[root] local_file.private_key (expand)" -> "[root] provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"]"

"[root] meta.count-boundary (EachMode fixup)" -> "[root] local_file.private_key (expand)"

"[root] provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"] (close)" -> "[root] local_file.private_key (expand)"

"[root] root" -> "[root] meta.count-boundary (EachMode fixup)"

"[root] root" -> "[root] provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"] (close)"

}

}

If I “pipe” this through a filter for drawing directed graphs:

terraform graph | dot -Tpng > graph.png

I get a nice image of a graph as seen in Figure 1. (I’ve also inverted the colors with imagemagick)

Getting to know a specific technology or a tool is not as easy as it seems. Hopefully, this blog post will make some of the unusual Terraform options clearer and more usable.

If you enjoyed this blog post, please share and spread it. For any suggestions or questions, contact me at nikola@cloudlad.io.