If you’re going to do operations reliably, you need to make it reproducible and programmatic. — Mike Loukides

This piece was originally published on Nikola’s blog cloudlad.io.

Terraform

Terraform, the de facto configuration tool for managing infrastructure nowadays, has come a long way since its early release, roughly 5 years ago. After many iterations, mostly driven by vocal supporters, one of Terraform’s biggest strengths, listening to its community, has proven crucial to its success.

This blog post is going to be about how I practically apply Terraform’s 0.13 features into one of the major IaaS providers Google Cloud.

The Scenario

Having worked with both AWS and GCP, I have found that as usual, there are pros and cons to both cloud providers.

One slightly simpler thing (perhaps better) than the other cloud providers is the coupling between G Suite and GCP. G Suite acts as a central identity store that we can use in GCP’s Cloud Identity and Access Management (IAM). The coupling between the users in a company and its IaaS provider simplifies the management overhead. As an example, one can use G Suite emails or email groups to assign permissions to resources within GCP. This leads to interesting combinations that clearly define responsibilities, and we benefit from heightened security because of said segregation of roles and duties.

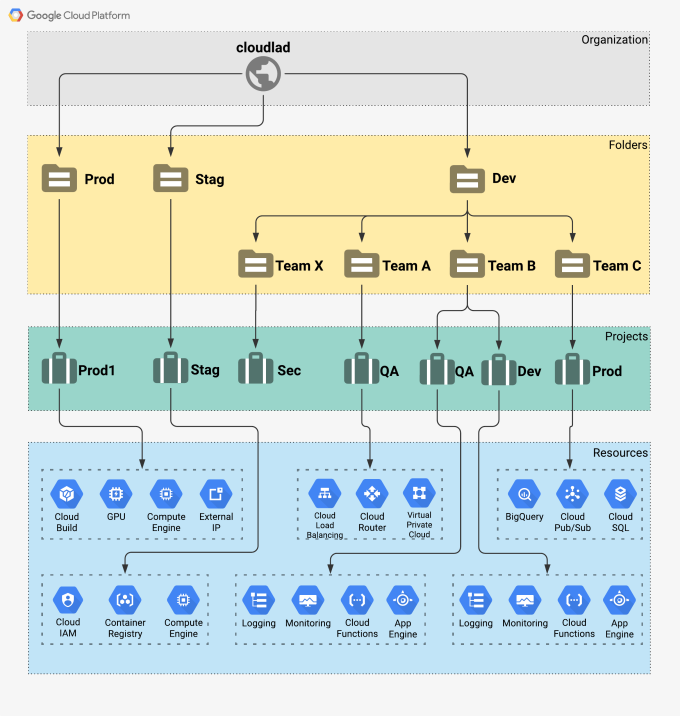

Google Cloud has a concept of Cloud Platform Resource Hierarchy. This enables the operator to control and fine-tune ownership, access control, and inheritance. An organization is the root node of the hierarchy. Then come the folders and the projects. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cloud Platform Resource Hierarchy

Let us assume the following case. There is a big organization with many engineering teams that need isolated testing environments. The security team that needs to supervise the teams and their respective resources needs to have a project to deploy its tools. This is to provide support in the unlikely case of security issues that might arise.

A Folder can have many other folders and projects below it. Besides, access to the resources within the projects can be limited by Folder so that an IAM email (user, group, or a service account) can have a set of permissions for the Cloud resources living within a Folder. With some planning, the hierarchical structure of an organization can be fascinating.

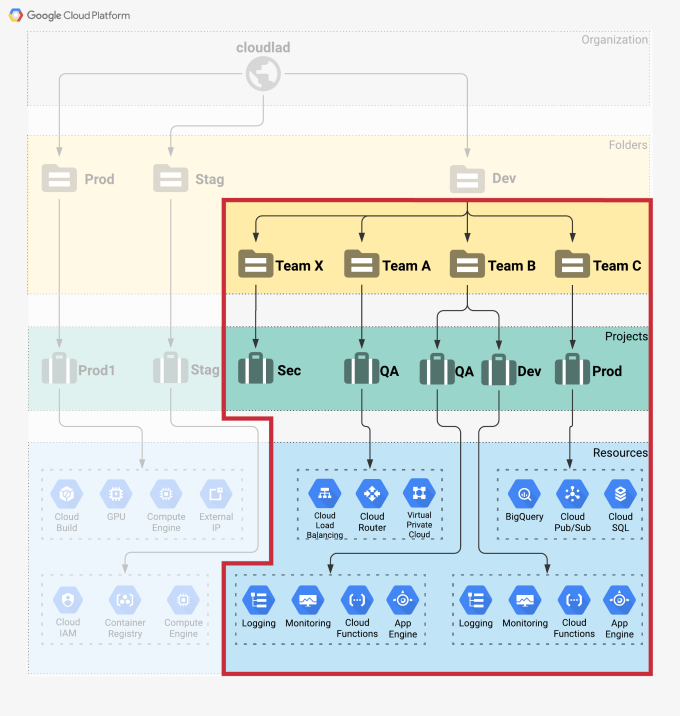

For simplicity’s sake, I will limit the example with only a subset of the resources. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Subset of resources

From this point on, the reader should be comfortable working with Terraform.

count And for_each For Modules

The count and for_each features enable us to have a systematic creation of multiple resource instances with a single configuration block. With previous Terraform versions, it was not possible to use these arguments with modules. Starting from 0.13, these powerful meta-arguments for workflows add up to the already extensive list of Terraform’s features.

Both count and for_each can be used interchangeably. I prefer for_each because the resource instances in count are identified by their index in a list. If we remove an element from the middle of the list, every item after it would require a re-creation. Read more in the official Terraform documentation.

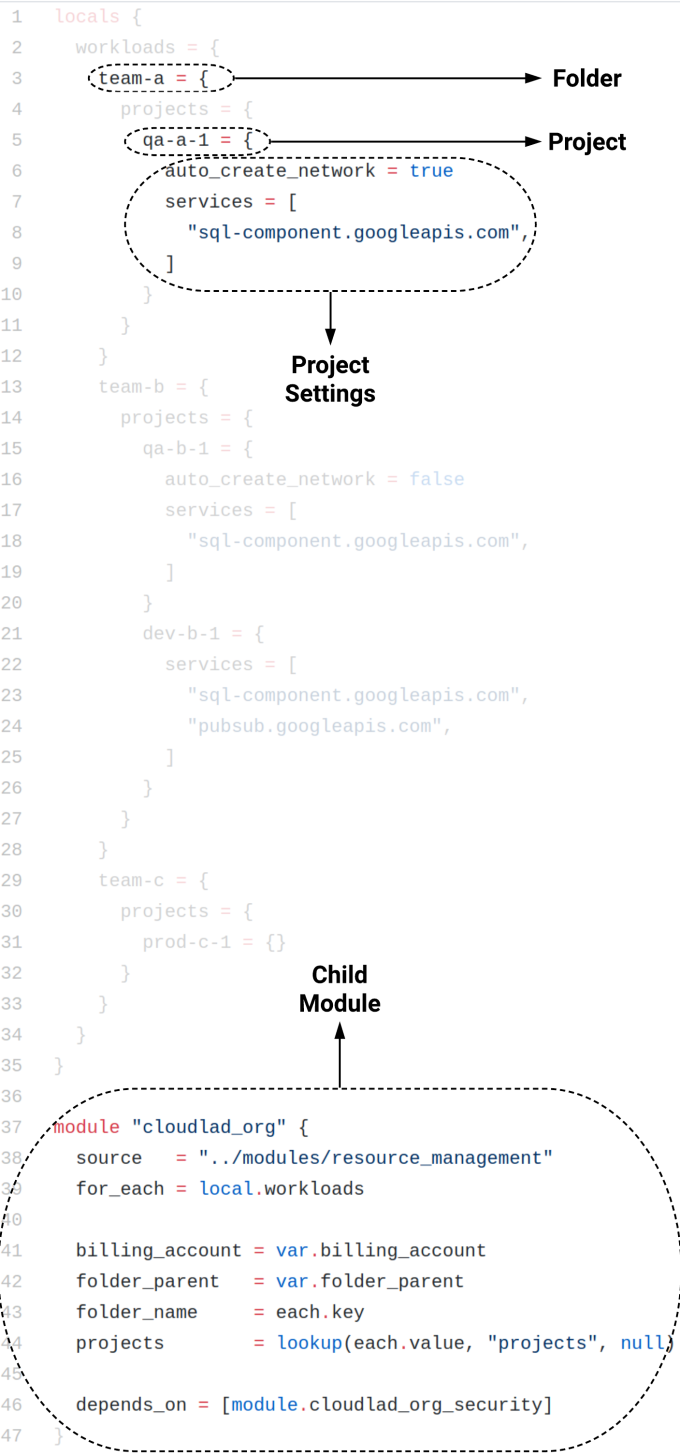

We can set a local map variable in the root module that defines the creation of our resources, bundled inside the child module. See Figure 3.

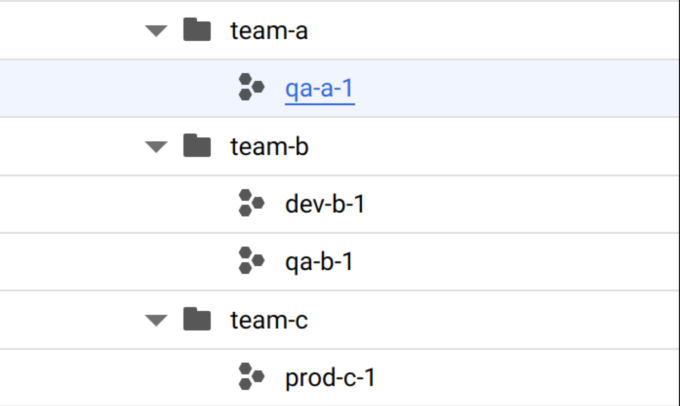

This Terraform configuration will create three folders and four projects. See Figure 4.

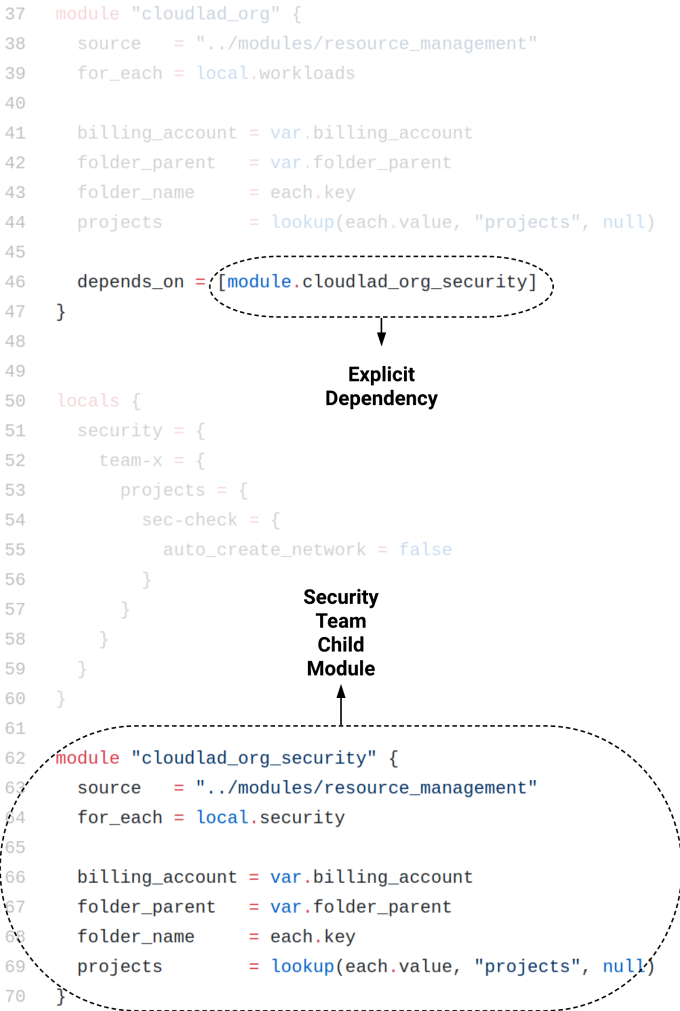

depends_on For Modules

Provisioning APIs is a sophisticated business. Sometimes the APIs do not behave as we expect them to, or often they lack features. Managing resources in the cloud adds to the complexity plus sometimes we require working with the resources in a specific order. The depends_on meta-argument addresses the issue.

There are two types of resource dependencies in Terraform, implicit or explicit. Implicit dependencies are handled by Terraform automatically. It analyses expressions within configuration blocks for references to other resources. As an example, a VM instance will implicitly depend on the resource defined in the network_interface setting, because it requires an IP Address to operate.

Sometimes, though, Terraform cannot resolve some dependencies on its own. In such a case, we explicitly set them with the depends_on meta-argument.

depends_on was originally available for resources only, from version 0.13 onwards it is available for modules as well.

Let us suppose that the security team in our organization wants to have an overview of all the resources that are present along with their activity. For that, a separate GCP project would suffice. The only requirement for this project is that it needs to be created before the others (and configure its tooling accordingly). From Terraform’s perspective, all the other projects depend on this project, which I dubbed “Team-X”. See Figure 5. Explore more on the topic of dependencies confusion attacks.

Custom Validation Rules

Terraform’s parameters, also called input variables, have type constraints by default. Version 0.13 offers an additional feature with which I can validate the content of the input variables.

The variable block supports an additional validation configuration that has a condition parameter that checks if an expression is true or false. Its usage varies depending on the variable.

In the example below, I am validating the required input variable billing_account. Google Cloud’s billing accounts have the form of six alphanumeric characters, separated by a dash sign.

variable "billing_account" {

description = ""

type = string

validation {

condition = can(regex("^[[:alnum:]]{6}-[[:alnum:]]{6}-[[:alnum:]]{6}$", var.billing_account)) error_message = "Invalid billing account, please provide a valid billing account in the following format "XXXXX-XXXXX-XXXXX"." } }

The validation above checks for a valid Google Cloud billing account and fails if the regex doesn’t match with the provided input variable. The content in the “error_message” argument is being displayed on stdout. Example with an invalid billing account.

$ terraform apply

Error: Invalid value for variable

on main.tf line 66, in module "cloudlad_org_security":

66: billing_account = var.billing_account

Invalid billing account, please provide a valid billing account in the

following format "XXXXX-XXXXX-XXXXX".

This was checked by the validation rule at

../modules/resource_management/variables.tf:5,3-13.

Terraform’s feature list does not stop here. There are many others, but I decided to write only about the most notable ones. For a full list of features and fixes head on to Terraform’s release changelog.

I hope that this blog post helped you in understanding how a basic hierarchical setup in Google Cloud can be achieved with Terraform. Please share this post if you find it interesting and helpful. Read more about this topic with a Security Overview of Google Cloud Platform.

The example module that I am using in this blog post can be found here.

Nikola is a Senior Infrastructure Engineer at Cobalt with more than 13 years of experience in managing infrastructure, 7 of which he spent specializing in IaaS. He’s a Certified Terraform Associate and a Hashicorp Ambassador, and you can find more of his thoughts on Google Cloud Platform management on his blog cloudlad.io